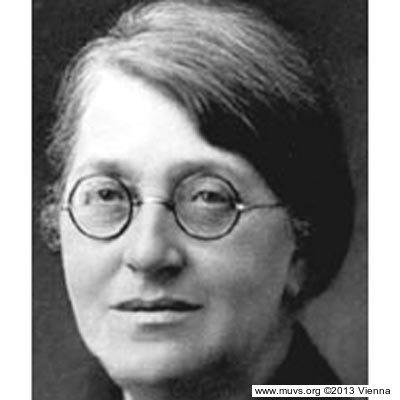

Margret Hilferding (1871-1942)

In the 1970s, the feminist movement argued that problems considered ‘typically male’ would have been solved long ago or made out to be ‘national missions’, in contrast to those that are ‘typically female’, examples being difficulties that involve menstruation and abortion. Being ‘typically female’, there was no rush to find solutions. Austria can be seen as a confirmation for this argument: Half a century passed before the calls for legalising abortions during the first trimester were finally met.

An early supporter of these efforts was the Austrian teacher, doctor and follower of individual psychology Margarethe Hilferding, née Hönigsberg (1871-1942). At a May 1924 conference of the Association of Vienna’s Social Democratic Doctors (Vereinigung sozialdemokratischer Ärzte Wiens) on abortion and population policy, she and her fellow female party members clashed with Vienna’s municipal councillor for health at the time, Julius Tandler. He too supported abortion, though his reasons were entirely different: Tandler insisted that abortions be legal only in the presence of ethical, eugenic or social reasons.

Women are still waiting for another of Hilferding’s demands to be met: “In the interests of social medicine she demanded that health-insurance funds pay for contraceptives and that abortion be legalised, which would eliminate the ‘violence done by laymen.’ ”

Another matter that’s still relevant is her idea that “a society’s right of veto with regard to offspring could only be justified if the society assumed all the costs and responsibility for this offspring.”

Hilferding’s work also advanced the women’s rights movement – though she herself owed a great deal to it: when the question of her education came up, women had few options. For this reason, she began attending the Austro-Hungarian monarchy’s teachers college at the age of 18, though this path was not her first choice. During this time, she read August Bebel’s Das soziale Elend und die besitzenden Klassen in Österreich (“Social Poverty and the Propertied Classes in Austria”) and developed a social and feminist outlook.

Hilferding originally wanted to be a “doctor in a working-class district”, but women were not permitted to attend Austrian universities as regular students until 1898, and then solely in the humanities. Margarethe Hilferding was one of the first to do so. Beginning in 1900, women were finally permitted to study medicine, and at the age of 32, Hilferding was the first woman to obtain a PhD in the field.

Hilferding began working as a doctor in 1910, after her two sons were born and after separating from her husband, the doctor, economist and Austromarxist Rudolf Hilferding, who was later the Weimar Republic’s minister of finance. She practiced medicine in Vienna’s working-class 10th district and worked in addition as a school doctor from 1922. As well as practising medicine for many years and being a single mother, Hilferding performed scientific research and gave lectures and courses on social and educational policy, particularly woman’s issues, sexuality, birth control, and sex and general education. In 1926, her book entitled Geburtenregelung (“Birth Control”) was published, through which Hilferding called for liberalisation of the abortion law. In 1942, she died on the way to a concentration camp.

Quotes taken from: Eveline List, Mutterliebe und Geburtenkontrolle: Zwischen Psychoanalyse und Sozialismus. Die Geschichte der Margarethe Hilferding-Hönigsberg, 2006